Welcome to the ClinicalEVIDENCE newsletter.

We aim to share with you the most up-to-date clinical data about heart diseases, diagnostics and monitoring in a brand-new series of content.

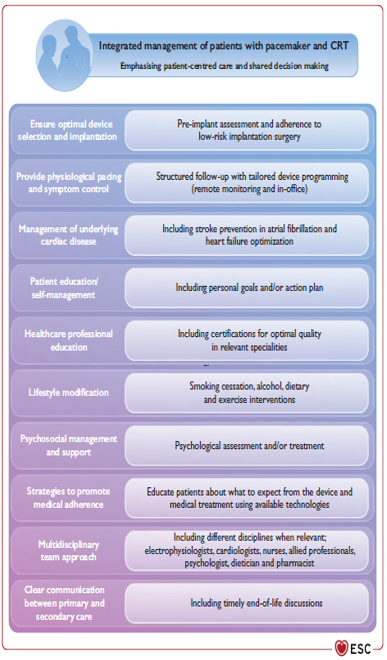

As a whole, our mission is to inform you of the most recent and cutting-edge developments in this field and to give you a better understanding of how to manage heart failure using the most advanced methods and technologies.

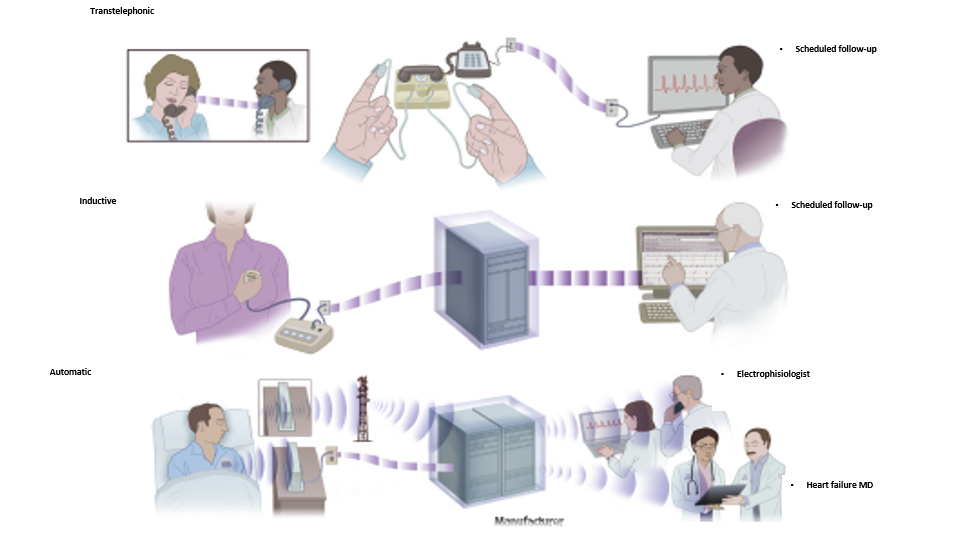

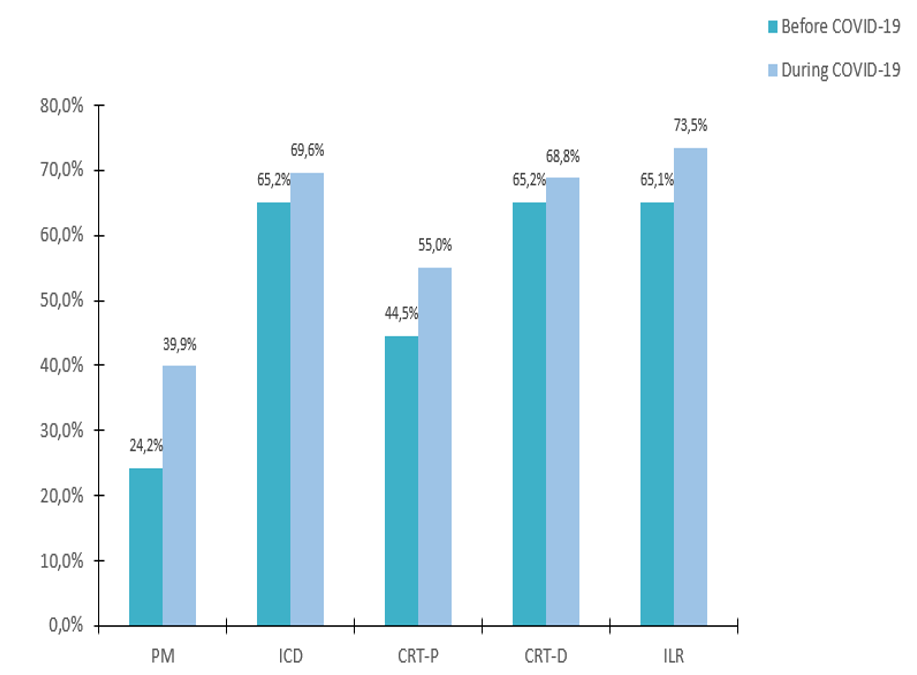

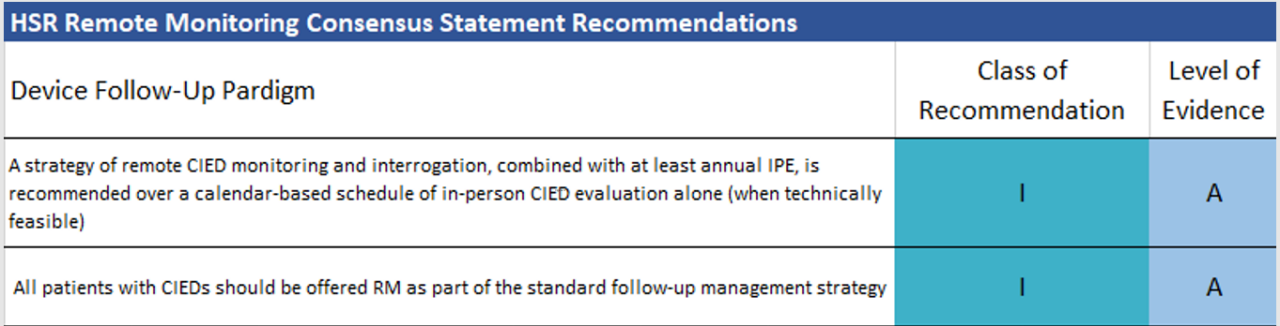

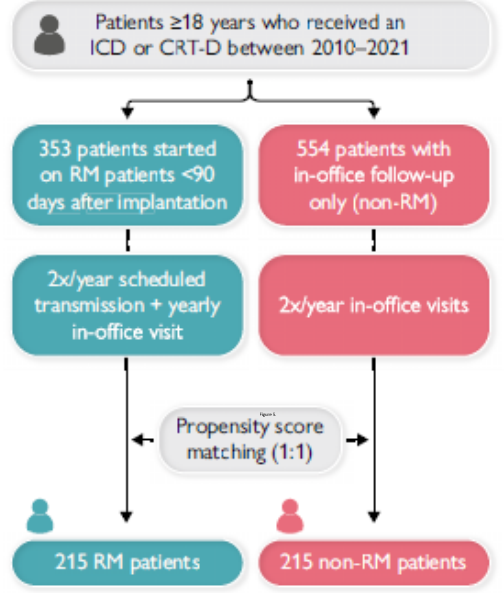

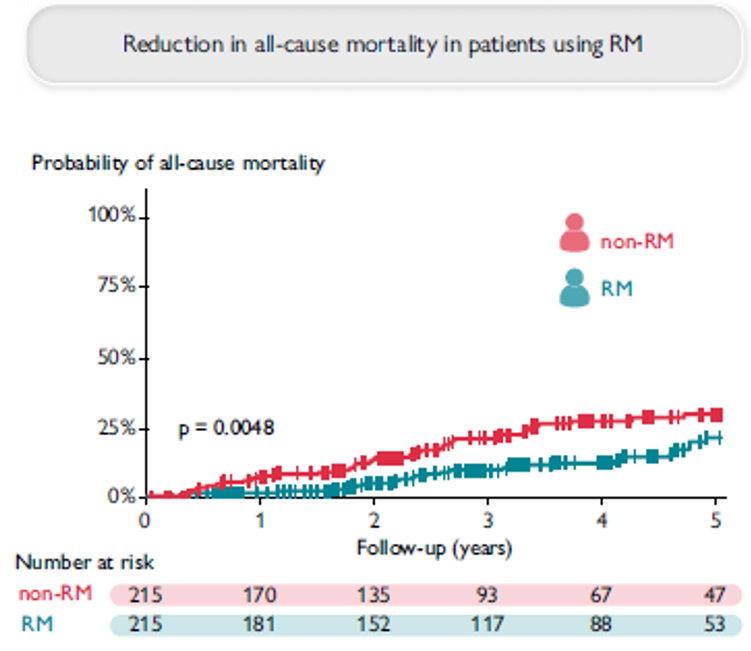

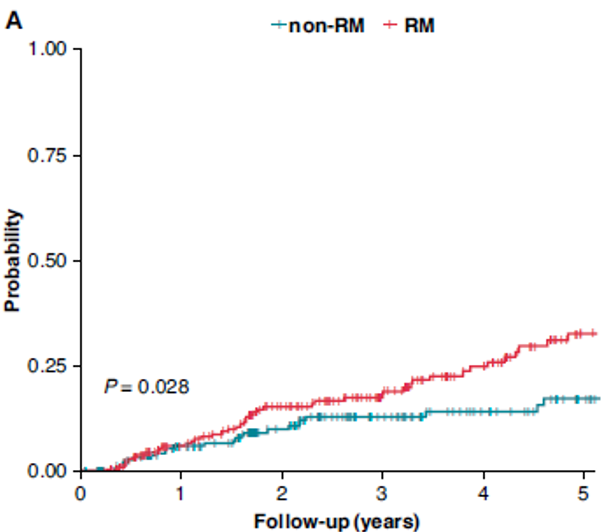

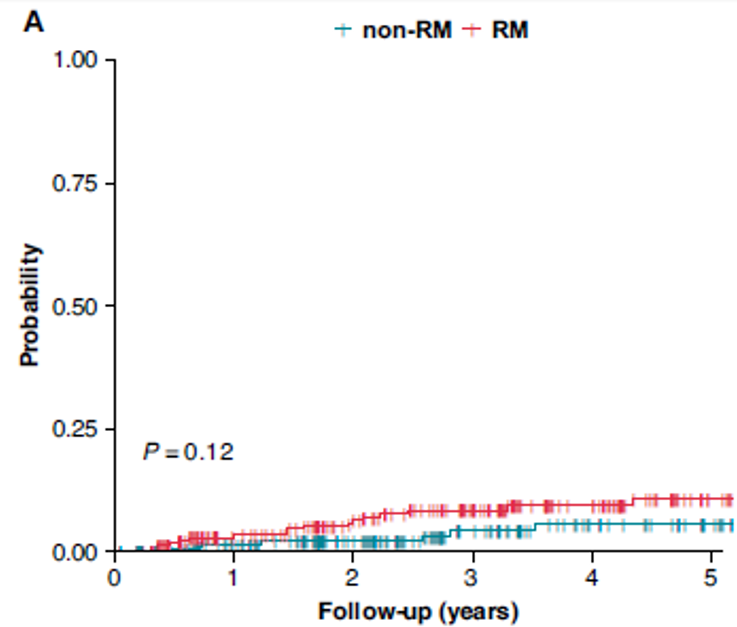

Remote Monitoring is the focus of this issue. We hope you will find it of interest.